STADTPFEIFER AND MUSIC IN LEIPZIG

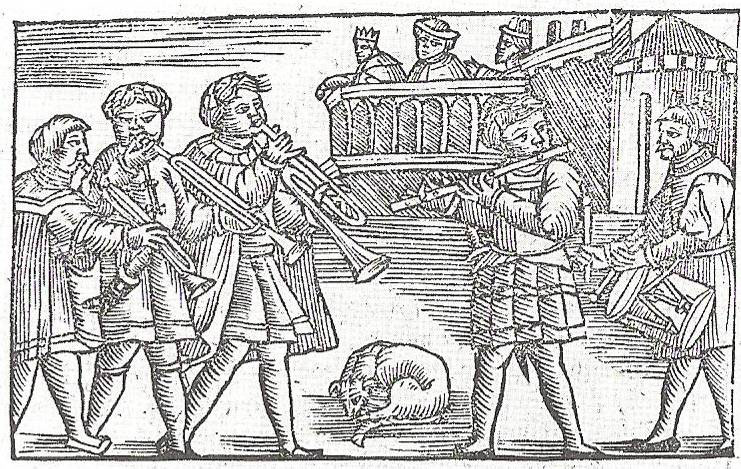

Municipal wind bands played a significant role in the cultural life of German cities during the Baroque. Most of these town musicians came under the jurisdiction of the town council and were known as Ratsmusik--Rat being the German word for council. The Stadtpfeifer were the paid musicians whose primary duty was to play concerts from the town hall tower at various times of day (thus the name "tower music"). They also participated in religious and civic ceremonies, played for dances, and alerted the town to the approach of an enemy or an outbreak of fire.

The reasons for this particular German practice were at least twofold. First, the public held wind music in high esteem, deeming it a particularly noble sound. Second, Germany was still a fragmented country with many smaller kingdoms and city-states, each responsible for the social, cultural, and physical life of its people. So the Ratsmusik provided a public relations opportunity to enhance the cultural life of the community.

Winds vs. Strings

Into the middle Baroque, wind playing was still held in the highest regard. The music of brass instruments reminded the Baroque citizen of royal splendor, processions, and promotions, while string music was indicative of the dance floor or the private home

The city of Leipzig retained records of various practices of the Ratsmusiker that provide insight into the music practice of the time. By 1650, the devastating toll of the Thirty Years' War was at an end, and Germany was finally able to return to the cultivation of commerce and artistic pursuits. Leipzig was about to enjoy the greatest century of its music history. Initially four Stadtpfeifer were employed as Ratsmusiker, serving primarily as wind players.

In time three more musicians, referred to as Kunstgeiger, were hired to play the violin. Surviving records reveal much squabbling between the two groups, mostly due to the perceived inconsistencies felt by the Kunstgeiger who were subordinate to the Stadtpfeifer. The Kunstgeiger were considered apprentices to the Stadtpfeifer and were often exploited for the sake of money, having to endure an income below that of their superiors. Jealousy was the common denominator as the Stadtpfeifer, being the privileged group, received first choice for engagements outside their required duties. On occasion these two groups would band together to fight the competition presented by the Bierfiedler (fiddle players employed by beer halls). During this time string players were often considered second class citizens when compared to wind players. By 1700, another class of musician, the NeuKirchenmusiker (new church musicians) made the situation even more complicated for the city council.

Since the Stadpfiefer and Kunstgeiger were trained simply as craftsmen, the Ratsmusik lacked the respect that organists and cantors enjoyed due to their liberal arts education. Kuhnau wrote that among one hundred Kunstgeiger, there could hardly be one who could write ten words without making a mistake, and Mattheson also had little regard for them, noting their perceived conceit and lack of education.

In Leipzig the four Stadtpfeifers' most important regular function was to play daily from the tower at city hall at 10:00 a.m. and at various times during the evening. This function was known as Abblasen or Turmblasen. Johann Pezel, perhaps the most famous of these Stadtpfeifer, noted in the dedication of his Hora Decima that this custom was of Turkish or Persian origin, then hastily confirmed that it had now become a Christian tradition. Gottfried Reiche noted that this tower music was a symbol of joy and peace--no doubt a reference to the peace enjoyed due to the end of the Thirty Years' War. Since the brass instruments were provided for this function by the city, both the instruments and the music were stored in the tower. For outside employment, musicians had to provide their own instruments.

In addition to the provision of music and instruments, the Ratsmusiker enjoyed other privileges, including weekly salaries, occasional extra money, and clothing. Also, until 1717, the Stadtpfeifer paid no taxes and were given free living quarters in the Stadtpfeifergäszlein (little city musician street) where they and their families all lived together in one house. While the rank of Stadtpfeifer was a lifetime position, the downside was that upon the player's death, the surviving family could be left without means of support. Also, income was precarious during times of mourning or pestilence, as music for celebrations such as weddings was curtailed for a prescribed period of time.

On occasion, if not regularly, the Stadtpfeifer joined with the Kunstgeiger under the direction of the Cantor for church performances. Because of their versatility in playing both wind and string instruments, the combination of the two groups of musicians, coupled with student players, allowed the Cantor a respectable orchestra with which to work.

When a musician applied for a position as a Stadtpfeifer, a complete knowledge of the Stadtpfeifer instruments was usually required. These could include trumpet, cornett, trombone, French horn (in time), bombart [German for shawm], dulcian [early bassoon], flute, oboe, plus strings. Little is available today as to textbooks or written instructions concerning the craft of the Stadtpfeifer due to the secrecy surrounding the guild. Indeed, it was most difficult to reach a high level of maturity, unless fellow musicians provided the training. Not until the Ratsmusiker tradition began to die did the first known text appear, written by Johann Ernst Altenburg.

The eventual decline of the Ratsmusiker movement can be attributed to a couple of factors:

1. The steady influx of free and independent musicians gradually took its toll. These "strolling musicians", as represented by the Bierfiedler (violinists playing in beer halls and taverns, Dorfmusikunsten (village musicians), Schallmeyer (shawm players), and Hümpler und Stümpler ("bunglers and blunderers", a reference from their guild-slang), played at weddings, parties, and christening feasts. They were not subject to the limitations of the municipal prohibitions and could earn a salary throughout the whole year.

2. There was an influx of concerts and opera performances into the city. At first, the Ratsmusiker would supplement the ranks of musicians in local concerts and the nucleus of the traveling opera company. However, in the local concerts, their honored position was gradually lost as they associated professionally with the very people whom they formerly had ignored. Also, in the opera, it became awkward to expect to augment the traveling orchestra, which had already perfected the playing of increasingly demanding scores. In time only the tower playing carried on.

Examples of repertoire performed in Leipzig no doubt included Pezel's Hora decima musicorum Lipsiensium (1670) written for five-part cornett and trombone ensemble, and Reiche's Vier und zwantzig neue Quatricinia (1696), written for four-part cornett and trombones. There was certainly a wealth of other literature written during the time as evidenced by the inventory lists from 1747 which included five chorale books and 122 wind pieces written by Gottfried Reiche which are now lost.

For more information, visit the parent page A History of the Wind Band also by Dr. Rhodes.

Also see these Wikipedia entries on Alta Capella and Waits.

No comments:

Post a Comment